Before the start of every game, senior Sam Hoegle warms up, drinks from her water bottle, and participates in a team huddle with the rest of the girls’ varsity soccer team. However, unlike the other players, Hoegle sports a Full90 Premier Headguard to protect her in the case of any injuries. Hoegle has worn the headguard for over a year, after a dangerous incident in which she was simultaneously hit in the face with a ball as well as hit on the other side of her head by another player’s arm.

“I started wearing it after I got my second concussion,” Hoegle said. “My concussions weren’t really that bad, but I just didn’t want to get another, worse one.”

Concussions are prevalent in many contact sports, particularly football, and are a type of traumatic brain injury that shakes the brain inside the skull and causes it to bruise. Until recently, however, concussions caused by soccer collisions didn’t seem to get much media attention.

In 2012, the National High School SportsRelated Injury Surveillance Study reported 92,171 concussions in high school soccer for the 2011-2012 school year.

Symptoms of concussions vary and include headaches, dizziness, fatigue, drowsiness and visual and balance problems. Athletes should seek urgent care when they suffer from slurred speech, seizures and neck pain.

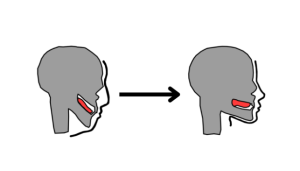

Often times, concussions are the result of getting hit in the head by another player’s head or limbs, or falling on the ground head first. However, recent studies have shown that “headers,” or hitting the ball with one’s head, can lead to head trauma and possibly result in concussions through numerous subconcussive blows.

According to a study published in late 2012 in the Journal of the American Medical Association by Dr. Inga Katharina Koerte, a neuroradiologist at Harvard University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, soccer players who repeatedly hit the ball with their heads may cause damage to their brains, even though it may not result in a concussion.

Koerte examined brain scans of a dozen German professional soccer players and found a pattern of damage to their brains that had a strong resemblance to the brains of patients with mild traumatic brain injury.

Using diffusion tensor imaging, a high-resolution MRI technique, researchers saw changes in the frontal, temporal and occipital lobes of the brain, regions responsible for higher order thinking, memory, attention and visual processing. Koerte’s team observed that the white matter, the interior portion of the brain that carries signals from nerve cells to the spinal cord, had suffered damage and could not restrict the movement of water molecules within the brain tissue.

“Given that soccer is the most popular sport in the world and is extensively played by children, players should be aware that they may be putting themselves at some risk for developing brain injuries,” Koerte said. “Our results should be taken into consideration in order to protect soccer players, and limiting of heading the ball may be one thing to be discussed.”

A new study led by neurologist Anne Sereno published in late February, researched the effects of headers on 12 female varsity soccer players through an iPad app measuring the cognitive function and response time of the players after practice and 12 female non-contact sports athletes. The tests displayed 30-to-50-millisecond changes in response time, which is in line with mild traumatic brain injury.

Roughly 40 percent of soccer concussions are the result of collisions between players, while approximately 13 percent are due to headers, according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

At Jefferson, six of the 25 head injuries in boys’ and girls’ soccer since 2010 were due to headers, while eight were head-to-head injuries. Four injuries, all from goalies, were the result of being kicked or kneed in the head.

Senior Chris Piller, a goalie for the varsity boys’ team, recently suffered a concussion at a game against Falls Church High School on March 11. After he dove to get the ball, the Falls Church forward kicked him in the head.

“As a goalie, I don’t generally head the ball,” Piller said. “However, I am taking time off of practice and games and getting rest.”

Junior Seong Jang was hit in the head by a soccer ball during his freshman year, when a senior practicing corner kicks accidentally kicked the ball into his head. Jang suffered a concussion for approximately three weeks.

“The obvious danger with heading the ball would be that it can cause trauma to the head,” Jang said. “However, of all the players I know, most of them got their concussions by being hit unexpectedly or clashing heads with another player rather than by heading a ball.”

Female soccer players are twice as likely to get concussed as males, according to a study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that in high school sports, football has the highest number of brain injuries, while girls’ soccer is second highest.

“The girl’s neck is usually thinner and weaker than a boy’s, so the head will move more under impact,” varsity girls’ head coach Luis Gendive said. “Heading technique is part of prevention, because too many players don’t know how to head the ball properly.”

At Jefferson, athletes are monitored everyday by the athletic trainer through impact tests and symptom checklists, and are excused from school work, homework and sports participation. Athletes here typically take 14-31 days to recover from concussions and follow a five-stage return-to-play protocol.

Sophomore Stav Nachum suffered a concussion at a travel game on March 23, when she was hit at the back of her head by another player, causing her to fall forward and hit the front of her head on the ground.

“I don’t remember much of what happened, but that’s what my teammates and coach said happened,” Nachum said. “I’m currently still recovering from my concussion by resting from sports and not doing anything too strenuous on the brain.”

To protect themselves from head injuries, athletes have the option to wear headguards. Full 90 Sports, Inc. is currently the largest global manufacturer of headguards, and produces the Full 90 Performance Headguard, which Hoegle wears. Several professional soccer players also sport headguards during games, notably Petr Cech, the goalie for the Chelsea Football Club in the Premier League.

The headguards meet and comply with FIFA, US Soccer and National Federation of State High School Associations regulations. A study conducted by Scott Delaney of McGill University found that players not wearing protective soccer headgear were 2.65 times more likely to suffer a concussion than those who did, and also stated that the frequency of lacerations, contusions and abrasions was reduced in players wearing headgear.

“I like the headguard because I’m definitely not as worried anymore,” Hoegle said. “It does help absorb impact and keeps me from worrying as much.”

However, many athletes who have suffered concussions continue to play soccer without the protection offered by the Full 90 Performance Headguards.

“Athletes will sometimes be unsportsmanlike and go after the players wearing headguards, since they’ve usually already had a concussion before,” athletic trainer Heather Murphy said. “Because of this, a lot of kids won’t wear the headguards because they’re afraid the other players will go after them.”

While the tests conducted by researchers are too small to be considered definitive, the studies do show that repeatedly using your head to strike a ball may create some amount of damage, especially when headers are at much faster speeds.

“I think most of the head injuries are difficult to avoid,” Piller said. “Soccer is a very physical game, and there will always be strong competition to win headers.

(This article originally appeared in the April 12, 2013 print edition).