Asian students and the people of color debate

The drawing characterizes the debate over Asians being recognized as POC. Specifically, the shading of the image in different parts represents the contrasting viewpoints of Asians being grouped with white Americans or seen as POC.

February 3, 2022

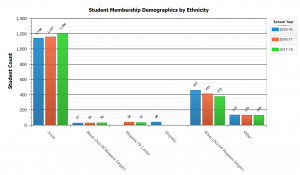

Asian Americans’ status as people of color (POC) has long been a subject of heated debate. In the past few decades, it has been a habit to associate Asians more with white privilege than POC’s struggle. In November of 2020, Washington school district North Thurston Public Schools (NTPS) infuriated many by separating Asian students from the student of color category and instead classifying them with white students in a school performance report. More recently, the University of Maryland (UMD) faced backlash for similarly grouping Asian students with white students and excluding them from students of color in admissions data.

While NTPS and UMD apologized for their insensitivity, they both justified their choice with similar explanations: grouping white and Asian students together allows for underrepresented groups to be more visible in data and for groups with fewer opportunities to be focused on. Underrepresented groups are rightly a necessary focus for schools; minority groups such as African Americans, Indigenous Peoples and Latinx Americans have faced a continuing history of systemic disadvantages and opportunity gaps. But this grouping of Asian and White students also plays into many stereotypes that Asian Americans are facing.

One of these stereotypes is the idea that Asian Americans have somehow broken the “minority barrier” and achieved success. More broadly known as the model minority myth, this stereotype falsely characterizes Asians as quiet, law-abiding and as proof to other ethnic and racial minorities that racial injustice can be beaten solely through hard work and determination. The categorization of Asian students with white students continues to make people believe that as the “model minority,” Asians can be generalized as overachieving and privileged. It assumes Asian Americans are similar to white Americans and are no longer facing disadvantages.

It’s because of this generalization and the view that racial discrimination no longer affects Asians that many people perceive Asian Americans as “honorary whites,” a label originating back to South Africa’s apartheid. For decades, everyone, including Asian Americans themselves, have been convinced that Asians are doing great in the American system when in reality, Asian American students have one of the highest suicide rates in the country and 32 percent of Asian American adults are in fear of being physically attacked or threatened because of their race, a higher proportion than any other racial or ethnic group. Despite their seeming success in the workforce, Asian Americans are the least likely racial group to be promoted into executive positions and Poverty levels in Chinatowns are overlooked over and over again.

The issue with the perception of Asian Americans’ proximity to white Americans in the hierarchy is that, in addition to driving minority groups apart, it also prevents Asian Americans from getting the help they need. The stereotype that all Asians do well in school is leading to teachers overlooking the needs of struggling Asian students compared to their counterparts. That’s why it’s important to acknowledge Asian Americans as POCs –– the racism they face is the opposite of insubstantial, as seen in COVID-19 hate crimes. The stereotype that they have broken through POC barriers is exactly what is hurting them.

It’s understandable that so many Asian and Asian American students, including myself, are upset by the actions of both NTPS and UMD and how the classification of Asian Americans as not students of color disparage the discrimination and challenges Asian Americans face. The seemingly innocuous display of demographics speaks to a far larger issue: a long, white-washed history of Asian Americans’ inability to speak up for themselves. Still, it’s important to know that these schools’ classifications were intended to highlight historically underrepresented groups. From this controversy, we should not be focusing on how hurtful the categorization was, but on how we can better understand and acknowledge the issues and the diversity within every group of people.

Ormond Otvos • Dec 25, 2022 at 2:34 am

As an 82 yr old who was a Merit Scholar/Science tAlent Search winner, I wonder if the TJ admins allow a story in this publication about the suppression of National Merit notifications to the recipients on the basis that it might make other students “feel ba”d?

Michael Eggert • Sep 17, 2022 at 3:52 am

Well done! I like all your points!….

If “white” people like me could choose a neighbor who is POC… we would always prefer Asian over Hispanic or black… but I’m concerned how few black people I know or are friends… so I am also guilty and work at being more inclusive… I’m almost 70… and still learning!

Tommy What is this? • Jan 29, 2023 at 9:02 pm

” but I’m concerned how few black people I know or are friends…”

never have I ever stared so hard imto my computer screen…..