Follies of standardization

Standardized tests are intended to create a fair testing environment for all students, but when in-class instruction and test preparation resources differ from classroom to classroom, this fairness can be compromised. It’s worth considering where test standardization is to Jefferson’s benefit, and where an unstandardized framework might be beneficial.

February 11, 2023

Believe it or not, not all teachers are homogenous. Teaching plans, styles, and even schedules shift from classroom to classroom. Some physics teachers might speed through the kinematics unit to make time to teach their students a touch of calculus, while others might spend several weeks on the CAKE equations alone. Students under the tutelage of Ms. Gilbert might be unfamiliar with the phrase “With focus comes depth, with depth comes complexity,” but students of Mr. Miller are well known to have copies of the maxim surgically affixed to their brains. So yes, teachers are not homogenous. Why do we test like they are?

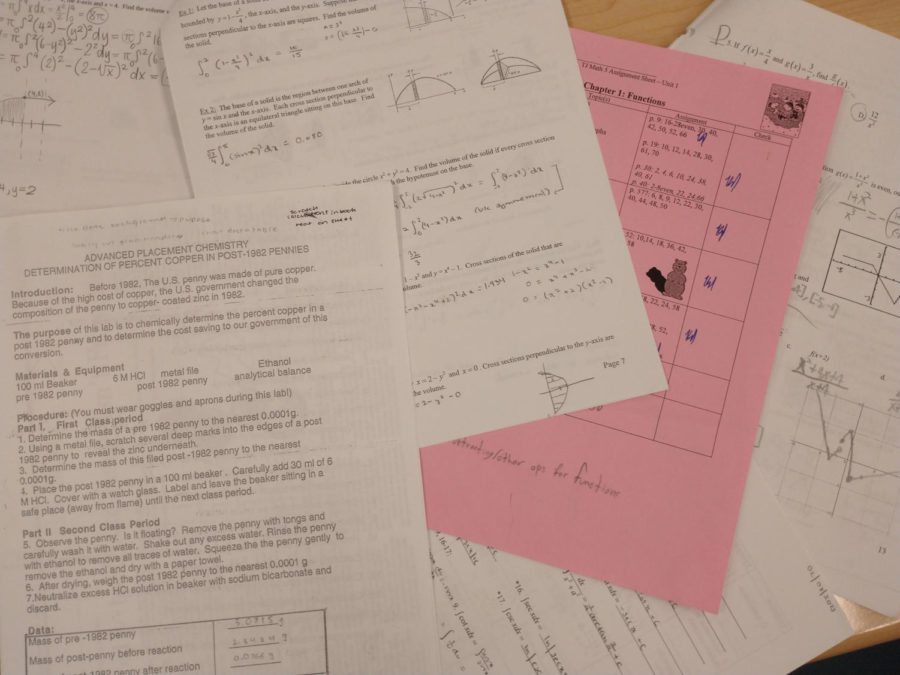

In this regard, I specifically refer to the chemistry and physics classes at Jefferson. During my time in Honors Chemistry, the majority of the tests I took deviated greatly from what we’d covered in class. I would routinely encounter vocabulary I’d never heard from my instructor or read in the textbook, and I wasn’t sure how to better prepare. Some students under other teachers had similar complaints, but not everyone. We’d all learned chemistry, but we’d learned slightly different material, and students with teachers who had written or taught based on the test consistently performed better than the rest of us. I might have been able to confidently draw up Lewis dot structures for the first 80 elements, but come testing day, I’d never even heard of a free radical.

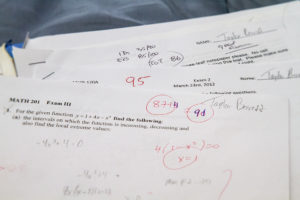

My physics class recently had a unit test that deviated from the material we’d learned so greatly that our teacher was forced to leave the room mid-test to discuss the issue. Our class averages totaled less than 50%, substantially lower than other testing groups.

For both of these examples, the issue was not that some teachers had taught better than others. Fields such as physics, chemistry, and biology have more foundational material than could ever be taught in a single year. Teachers are forced to make tough calls about what to cut, and when those calls are different, some classes of well-studied students end up bombing tests.

I do not mean to argue that standardized tests have no place at Jefferson. I have been continuously impressed by the tests put together by the teaching teams for Math 3, Math 4, and Math 5. By using standardized curriculum packets, these classes circumvent the issues caused when educators take different approaches to condense complex topics into brief units. Students who complete the assigned materials are usually exposed to any and all problem types that can be found on the tests.

Still, not all classes have the luxury of being able to teach the same material every year. Quantum might not have been worth prioritizing in Physics 1 30 years ago, but as of now, quantum computing is one of the most exciting and consequential fields in the modern world. In classes with shifting content requirements, the creation of new curriculum guides would be an incredibly time-intensive task that would put even more strain on our busy teachers.

My point is not that Jefferson should leave standardized tests behind. Instead, I would contend that we should rethink where we apply them. Standardized tests are supposed to give each student a fair shot at success. The problem is that one-size-fits-all tests can’t be fair if different classes learn different materials at different rates. Tests should be designed by people who know what the students have been learning, and if this requires a loss in standardization, so be it.

We can do better, so let’s start now.