Stop what you’re doing and watch ‘The Cranes Are Flying’ (1957) right now

The Soviets might not have won the Cold War, but they sure will win over your heart.

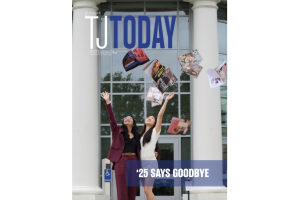

Veronika (Tatyana Samoylova) and Mark (Aleksandr Shvorin) walk through a war-torn Moscow in “The Cranes are Flying”.

September 20, 2021

I want you to think about what you want to watch next. Do you want to watch the new Marvel movie? Do you want to catch up with that zombie pop star anime your sister keeps telling you about? Maybe you want to just watch “La La Land” (2016) for the 15th time because it makes you cry and that’s just what you need right now. Well, whatever it is you’re thinking about, stop it, because you need to see “The Cranes Are Flying” immediately. Now I know that there might be some things about this movie which might initially scare you off, but let’s get to the heart of what I imagine is most intimidating: “The Cranes Are Flying” is a Soviet movie from the 1950s, so how could it possibly be interesting?

There’s a certain air to the culture of the late not-so-great Soviet Union which might justifiably lead someone to believe that their movies might skew to the boring side. That’s mainly because the film industry was controlled and heavily censored by the government. This is a perfectly reasonable point, and I can understand why that would make the Soviet film industry seem dull. On the other hand, “The Cranes Are Flying” was made at just the right time in history to make this control almost work in its favor.

For one, let’s address the government control over the film industry. For a long time in Soviet history, largely when Stalin was around, the Soviet film industry was creatively stifled on a mammoth scale. Stalinist film censorship had such an iron grip over what could and couldn’t be made that everything had to be made according to his taste. Unfortunately for the world of film, Stalin’s taste skewed towards a hyper traditionalist Soviet realism. In Soviet realism, there always had to be a clear hero and villain and the movie’s values had to directly contribute to the philosophy of the party. This was a major departure from the silent era, where the Soviets were probably the most important creative force in the world and revolutionized editing as we know it, with masterpieces like “Battleship Potemkin” (1925) and “Man with a Movie Camera” (1929) still considered as some of the best movies ever made.

Now, all of this is bad, but here’s the catch: Stalin died in 1953. Post Stalinist Soviet cinema was a veritable playground for filmmakers compared to the years beforehand, with all the benefits of having a global superpower funding your films and without the problem of having one of the worst men in human history dictate what you could or couldn’t put in your movie. That’s not to say that you could do anything you wanted – ideologically, films couldn’t explicitly differ from the values of the country – but the advantages of being given a blank check to make your movie were not lost on director Mikhail Kalatozov, who used his resources to tell an incredibly personal story on an enormous scale.

There’s something truly inventive about the way that the camera functions in “The Cranes Are Flying”. There’s a million different examples of this throughout the movie’s runtime, but I’ll highlight one scene. Near the beginning of the film, the young lovers Veronika and Boris are being threatened by the WW2 Nazi invasion. While Veronika wants Boris to get an exemption and stay out of the war, Boris has already enlisted himself into the Red Army. The next scene happens right before he leaves. While Veronika is running to meet her beloved before he’s carted off to war, the camera attempts to track her through the enormous crowd of enlistees and families wishing them goodbye. While the motion of the character is kept consistent, the focus of the scene is not, and the camera passes by countless smaller vignettes of other families and couples wishing each other goodbye, each contributing more to the tone of the scene and informing us of the emotional goals of the characters, while ironically preventing them from ever meeting again. This kind of sequence of simultaneous tracking and distraction in a crowd of hundreds happens many times during the film, and it’s honestly some of the most impressive filmmaking I’ve ever seen. The amount of coordination that would have to be involved in choreographing multi-minute long takes which each have dozens of moving parts on screen at a time is astonishing, but it was made possible because of the specific situation of the Soviet Union’s film industry.

This is the kind of thing which makes “The Cranes Are Flying” such a special and exciting film to discover for yourself. It’s a very simple romantic tragedy on the surface – a man and woman are separated due to the horrors of WW2, and struggle to keep the love alive during each others’ absence – but the film’s near avant-garde stylings on such a massive scale make an already heart stabbing story all the more powerful. The horrors of war on the Soviet homefront are made more striking by the fast editing and bombastic scale of the air raids. The romantic longing of the two leads just missing each other before they’re separated is made more gut wrenching because of the dozens of couples getting closure in their way. The bittersweet finale is made all the more complex by what seems to be an entire nation feeling the same way. I guarantee you that you’ve never seen anything quite like this, and that’s why I implore you to stop what you’re doing and just watch “The Cranes Are Flying”. You can stream the film on HBO Max or rent it on Amazon Prime.