‘The Green Knight’ (2021): A legend for the dishonorable man

How do you make King Arthur interesting? Stop talking about King Arthur.

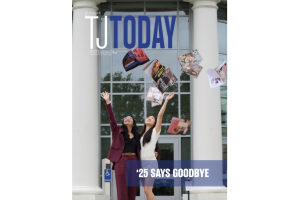

Dev Patel’s Gawain sits on a throne and has a crown lowered onto his head in the opening scene of “The Green Knight”.

September 1, 2021

Considering the current state of the Arthurian legend in pop culture, it seems fitting that the most compelling adaptation of the mythos since “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” (1975) casts one of the least flattering images of the eponymous king of Camelot. In “The Green Knight”, Arthur is old and withered and can barely even lift Excalibur. The years of legends are over, and what keeps the king going are retellings of tales from times long gone. What’s worse is that, as his kingdom decays, Arthur has no heir to the throne, which effectively spells out doom for any monarchy. But as the opening scene of the film tells us, this is not a tale about the king. Arthur and his Round Table must, for this new legend, take a back seat to the king’s dishonorable nephew, Gawain.

“The Green Knight”, an adaptation of the anonymously written “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (14th Century), is a lusciously captured and thoroughly captivating musing on the creation of myths. It’s a film which clearly shows its love for storytelling by not only adapting the Arthurian mythos for the modern day but also taking clear inspiration from folklore and cinema. For example, at various points, the film incorporates elements from the story of Saint Winifred and films like “Barry Lyndon” (1975) and “Ugetsu” (1953). It follows, of course, Gawain – who in this adaptation is not even a Sir – as he must make himself into a man worthy of legend. On a fateful Christmas day, Gawain is at the Round Table when the mysterious Green Knight appears to him and the other knights, carrying a formidable axe and a branch of holly. The knight challenges the men of the court to a game of sorts: strike the knight in any way, and then, in one year’s time, head to the Green Chapel to receive the same blow. For your trouble, you gain the knight’s axe. Gawain, seeing this as an opportunity to become renowned among his peers, slices off the Green Knight’s head, presumably inferring that a dead man can’t return the favor. Unfortunately for Gawain, that’s not the case. The Green Knight, upon having his head launched a few feet away from his neck, picks it up and tells Gawain that he has a year to live.

What follows is an epic journey of a man who seems, on all accounts, wholly unworthy of renown. Gawain completely disregards the chivalric principles – not being especially courteous or courageous, and certainly not remaining chaste – and hasn’t even earned his way into the ranks of the Round Table. He’s only there because of his familial relationship to Arthur. The film even points out Gawain’s worthlessness as a hero when Arthur asks him to tell a story of valiance, but Gawain has no such story to tell. Despite all this, or perhaps even because of it, Gawain’s story is still compelling. This is no longer the simple tale of the knight in shining armor we all know and love. This is the story of a man who wants to make himself worthy of those legends. Of course, virtue is never that simple, because in order for Gawain to be truly worthy of honor, he must die by the Green Knight’s axe… but in theory, he doesn’t have to. If Gawain returns alive, like his mother insists he will, he would still be honored by the people. In their eyes, he will have faced death and returned to tell the tale. This creates a fascinating conflict: Gawain must die in order to become honorable even though he would be rewarded for staying alive.

While the central conceit of the story is compelling on its own, what truly elevates it to greatness is pure sensory splendor. The score by Daniel Hart is mesmerizing. It takes inspiration from a range of styles, from gothic chants to folk songs to stringed pieces which almost sound like the ones in a horror movie. The color palette is equally diverse, from dark interior scenes lit sumptuously by orange flames to striking colored light that signifies moments of magic and abstraction. Along with this, the cinematography melds beautifully with the film’s editing rhythm in captivating ways. In the movie’s more lighthearted moments, conversations are shot in a manner I can only describe as quaint. The shots alternate between wides of the characters that almost capture the surrounding environment more than their performances. Conversely, when the film leans to its more moody and experimental side, the editing slows down, giving way to gorgeous long takes that allow the audience to soak in the magnificent composition and production design. This comes to a head in what might be the best shot in the film, where the camera languidly rotates 360 degrees clockwise to reveal Gawain’s worst possible fate, and then proceeds to rotate 360 degrees counterclockwise back to where he was at the beginning of the shot, now motivated to escape his predicament.

After all is said and done, what might be the most impressive achievement of “The Green Knight” is that it makes the Arthurian legend interesting again. While most filmmakers try to make classical myths palatable by turning them into action schlock that looks like wet pavement, David Lowery imbued a lesser known story with complicated themes and vibrant color to turn it into what might be the best film of the year. If you want to be wowed by some truly stunning visuals, moved by a simple yet effective narrative, or just want to look at Dev Patel’s pretty face, I highly recommend you seek out “The Green Knight”. You can catch it in theaters or rent it on VOD for $20.

P.S. If you don’t like how the movie ends, I suggest maybe staying through the credits. This film technically has two endings, depending on how long you stick around.