The children left behind

TJ Admissions process disadvantages disadvantaged students

February 9, 2018

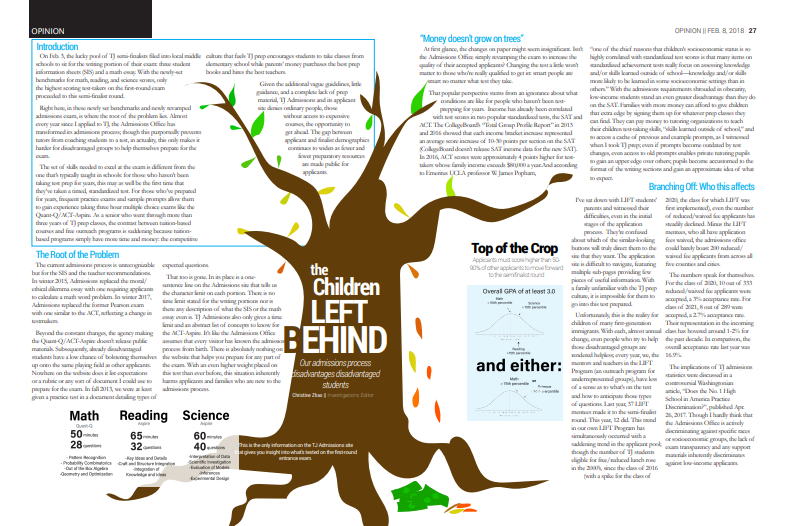

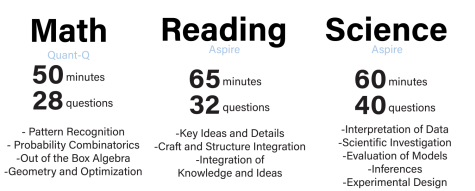

On Feb. 3, the lucky pool of TJ semi-finalists filed into local middle schools to sit for the writing portion of their exam: three student information sheets (SIS) and a math essay. With the newly-set benchmarks for math, reading, and science scores, only the highest scoring test-takers on the first-round exam proceeded to this semi-finalist round.

Right here, in these newly set benchmarks and newly revamped admissions exam, is where the root of the problem lies. Almost every year since I applied to TJ, the Admissions Office has transformed its admissions process; though this purportedly prevents tutors from coaching students to a test, in actuality, this only makes it harder for disadvantaged groups to help themselves prepare for the exam.

The set of skills needed to excel at the exam is different from the one that’s typically taught in schools: for those who haven’t been taking test prep for years, this may as well be the first time that they’ve taken a timed, standardized test. For those who’ve prepared for years, frequent practice exams and sample prompts allow them to gain experience taking 3 hour multiple choice exams like the Quant-Q/ACT-Aspire. As a senior who went through more than three years of TJ prep classes, the contrast between tuition-based courses and free outreach programs is saddening because tuition-based programs simply have more time and money: the competitive culture that fuels TJ prep encourages students to take classes from elementary school while parents’ money purchases the best prep books and hires the best teachers.

Given the additional vague guidelines, little guidance, and a complete lack of prep material, TJ Admissions and its applicant site denies ordinary people, those without access to expensive courses, the opportunity to get ahead. The gap between applicant and finalist demographics continues to widen as fewer and fewer preparatory resources are made public for applicants.

The Root of the Problem

The current admissions process is unrecognizable but for the SIS and the teacher recommendations. In winter 2015, Admissions replaced the moral/ethical dilemma essay with one requiring applicants to calculate a math word problem. In winter 2017, Admissions replaced the former Pearson exam with one similar to the ACT, reflecting a change in testmakers.

Beyond the constant changes, the agency making the Quant-Q/ACT-Aspire doesn’t release public materials. Subsequently, already disadvantaged students have a low chance of bolstering themselves up onto the same playing field as other applicants. Nowhere on the website does it list expectations or a rubric or any sort of document I could use to prepare for the exam. In fall 2013, we were at least given a practice test in a document detailing types of expected questions.

into what’s tested on the first-round entrance exam.

That too is gone. In its place is a one-sentence line on the Admissions site that tells us the character limit on each portion. There is no time limit stated for the writing portions nor is there any description of what the SIS or the math essay even is. TJ Admissions also only gives a time limit and an abstract list of concepts to know for the ACT-Aspire. It’s like the Admissions Office assumes that every visitor has known the admissions process from birth. There is absolutely nothing on the website that helps you prepare for any part of the exam. With an even higher weight placed on this test than ever before, this situation inherently harms applicants and families who are new to the admissions process.

“Money doesn’t grow on trees”

At first glance, the changes on paper might seem insignificant. Isn’t the Admissions Office simply revamping the exam to increase the quality of their accepted applicants? Changing the test a little won’t matter to those who’re really qualified to get in: smart people are smart no matter what test they take.

That popular perspective stems from an ignorance about what conditions are like for people who haven’t been test-prepping for years. Income has already been correlated with test scores in two popular standardized tests, the SAT and ACT. The CollegeBoard’s “Total Group Profile Report” in 2013 and 2016 showed that each income bracket increase represented an average score increase of 10-30 points per section on the SAT (CollegeBoard doesn’t release SAT income data for the new SAT). In 2016, ACT scores were approximately 4 points higher for test-takers whose family income exceeds $80,000 a year. And according to Emeritus UCLA professor W. James Popham, “one of the chief reasons that children’s socioeconomic status is so highly correlated with standardized test scores is that many items on standardized achievement tests really focus on assessing knowledge and/or skills learned outside of school—knowledge and/or skills more likely to be learned in some socioeconomic settings than in others.” With the admissions requirements shrouded in obscurity, low-income students stand an even greater disadvantage than they do on the SAT. Families with more money can afford to give children that extra edge by signing them up for whatever prep classes they can find. They can pay money to tutoring organizations to teach their children test-taking skills, “skills learned outside of school,” and to access a cache of previous and example prompts, as I witnessed when I took TJ prep; even if prompts become outdated by test changes, even access to old prompts enables private tutoring pupils to gain an upper edge over others: pupils become accustomed to the format of the writing sections and gain an approximate idea of what to expect.

Branching Off: Who It Affects

I’ve sat down with LIFT students’ parents and witnessed their difficulties, even in the initial stages of the application process. They’re confused about which of the similar-looking buttons will truly direct them to the site that they want. The application site is difficult to navigate, featuring multiple sub-pages providing few pieces of useful information. With a family unfamiliar with the TJ prep culture, it is impossible for them to go into this test prepared.

Unfortunately, this is the reality for children of many first-generation immigrants. With each, almost annual, change, even people who try to help those disadvantaged groups are rendered helpless to help; every year, we, the mentors and teachers in the LIFT Program (an outreach program for underrepresented groups), have less of a sense as to what’s on the test and how to anticipate those types of questions. Last year, 37 LIFT mentees made it to the semi-finalist round. This year, 12 did. This trend in our own LIFT Program has simultaneously occurred with a saddening trend in the applicant pool; though the number of TJ students eligible for free/reduced lunch rose in the 2000’s, since the class of 2016 (with a spike for the class of 2020, the class for which LIFT was first implemented), even the number of reduced/waived fee applicants has steadily declined. Minus the LIFT mentees, who all have application fees waived, the admissions office could barely boast 200 reduced/waived fee applicants from across all five counties and cities.

The numbers speak for themselves. For the class of 2020, 10 out of 333 reduced/waived fee applicants were accepted, a 3% acceptance rate. For the class of 2021, 8 out of 289 were accepted, a 2.7% acceptance rate. Their representation in the incoming class has hovered around 1-2% for the past decade. In comparison, the overall acceptance rate last year was 16.9%.

The implications of TJ admissions statistics were discussed in a controversial Washingtonian article, “Does the No. 1 High School in America Practice Discrimination?”, published Apr. 26, 2017. Though I hardly think that the Admissions Office is actively discriminating against specific races or socioeconomic groups, the lack of exam transparency and any support materials inherently discriminates against low-income applicants.

The Leaves: A New Beginning

TJ Admissions needs a wake up call to reality: every other testing agency’s model has proved to work. With CollegeBoard’s partnership with Khan Academy, CollegeBoard sought to “confront one of the greatest inequities around college entrance exams, namely the culture and practice of high-priced test preparation,” CollegeBoard said in a statement on March 5, 2014, two years before the new SAT launched. Hundreds of practice questions are available for public use and all eight practice tests from the Official SAT Study Guide are published on Khan Academy, providing those without means with the same access to practice materials. This has allowed both students and the CollegeBoard to prosper; six hours on Khan Academy increases scores by an average of 90 points and the number of SAT takers has risen by 15 percent. The CollegeBoard rebranded its SAT into a standardized test more approachable than ever, while every single time our admissions exam changes, it moves backwards.

The Admissions Office needs to provide more notice of any exam changes and free, comprehensive preparation materials for the redesigned exam, just like the CollegeBoard did. If the test makers still refuse to release materials publicly, then a possible compromise can and must be made: find another testing agency, provide reasoning for and details of the eventual change to the public, and work for two to three years to make the CollegeBoard standard a reality. Even the New York’s SHSAT (Specialized High School Admissions Test), long found to hold similarities to the Pearson admissions exam, provided a comprehensive 15-page document when it instituted a new exam in fall 2017 (with translations in multiple languages for those not fluent in English). This document fully detailed changes and answered frequently asked questions. Then, to follow that up, the NYC Department of Education released a 160-page student handbook with general directions, guidelines, and sample problems and tests. Though it doesn’t necessarily need to be as large scale as the Khan Academy/CollegeBoard partnership, the Admissions Office needs to offer a web platform somewhere in-between one sample practice test and Khan Academy’s individualized problem sets.

Right now it is offering nothing. And that needs to be fixed.

The movement begins with you. A change occurs when ordinary people speak up against the status quo. Take a few seconds or minutes to pen an email to the Admissions Office ([email protected]); bring up your own points or mention some of mine. We, the students, staff, and alumni, demand more transparency with clear-cut guidelines and a well-developed system of preparation. Our power comes from empathizing with the decreasing opportunities for future applicants, applicants, bright and driven, but underprepared for the system of exams, even when the ultimate effect bears no immediate effect on ourselves.